It’s an unfortunate reality that there were some unscrupulous people who put short term profit and illegal gain ahead of sustainable fishing and sustainable environmental practices. IUU toothfish activity had the potential to threaten not just legal fishing operators’ livelihoods, but also toothfish populations and ecologically related species such as seabirds, which were caught by illegal fishermen who did not adhere to the same environmental requirements as legal operators.

Each of these problems was, and is, cause for concern to governments, industry and conservation groups as well as the general public. Regulations and requirements for legal toothfish operators are stringent and are designed to ensure sustainable harvesting of toothfish populations, which promote sustainable fishing practices that avoid killing seabirds and mammals, and sustainable livelihoods for legal fishermen. Information regarding these stringent seabird related regulations can be found on our Seabirds page and more information on bycatch regulations and management actions for ecosystem based managed can be found from the CCAMLR website. Further to these regulations, CCAMLR annually reviews catch levels and implements limits on the legal take of toothfish, sets research requirements and programs for legal operators, and works to improve understanding of the stock and ecological linkages that exist in toothfish and other fisheries in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic regions.

In the late 1990s, industry members were instrumental, along with conservation groups, in setting up the International Southern Oceans Fishing Industry Clearing House (ISOFISH), which reported on IUU activity over a three year period. This group was funded variously from industry, conservation and government groups. The information gathered from both industry and conservation sources was compiled and distributed to governments and appropriate agencies to assist them to eliminate IUU fishing for toothfish. ISOFISH produced reports on IUU activity from Norway, Mauritius, and Chile as well as a report on how illegal operators were changing vessel names and ports of registration to avoid legal requirements such as the CCAMLR Catch Documentation System. So successful was ISOFISH that the IUU fishing dropped significantly by 1999/2000 and the group was subsequently disbanded.

Unfortunately, after ISOFISH members decided that sufficient profiling and assistance had been given to authorities to enable effective control over toothfish IUU fishing, the lack of an industry/conservation group “watchdog” saw increased activities by new, more highly organised IUU operators. These illegal operators believed they no longer had a significant risk of capture and/or public exposure for their illicit activities. Consequently, IUU fishing for toothfish saw an increase as newer, more organised, illegal operators began, or returned, to plunder populations of toothfish. In an attempt to quantify the IUU toothfish trade, several studies were undertaken by TRAFFIC, and these reports demonstrated that there was a substantial quantity of toothfish entering the trade from illegal sources, confirming what was already known by industry and CCAMLR Members. A powerful example of the sort of shift that has occurred in the type of operators involved in the IUU fishing activity was outlined in the COLTO report released in 2002, titled “The Alphabet Boats, a case study of toothfish poaching in the Indian Ocean” which outlined one group of IUU operations. Following this report, COLTO produced “Rogues Gallery – The new face of IUU fishing for toothfish” in October, 2003, and Australian journalists compiled an international investigative program on IUU fishing for toothfish, released on the ABC called “Toothfish Pirates”.

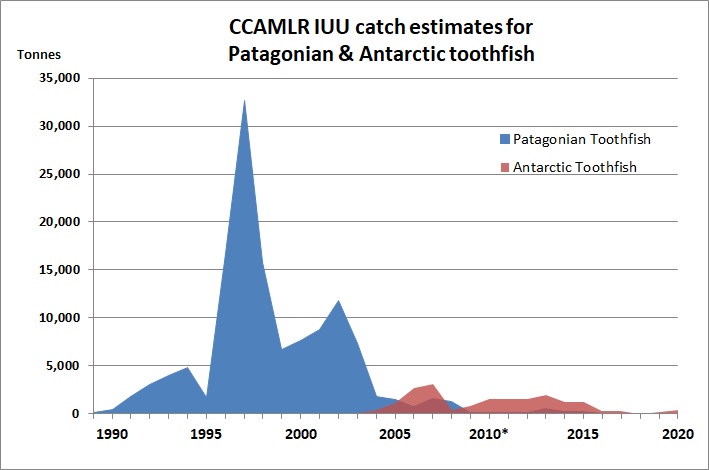

The period between 2005 and 2014, saw a shift in IUU operations, as they were pushed out of national EEZs, thanks to the actions mentioned above. These vessels moved further south into international waters and began to target Antarctic toothfish. They also switched their fishing gear from longlines to gillnets, which is a much more indiscriminate method of fishing. This period saw the number of IUU vessels severely decline from peak levels, and hovered between 5 and 10 for much of this time.

The remaining IUU operators continued to find loopholes surrounding high seas fishing, until the environmental group Sea Shepherd, announced Operation Icefish in 2014. This brought much needed public scrutiny to the case, and eventually found the support of INTERPOL, who issued a number of Purple notices to the remaining handful of IUU vessels, which all have now either been arrested or sunk.

COLTO remains vigilant in this space, and while there has been no sightings of listed IUU vessels in the CCAMLR area in several years, there has been a very small volume of IUU Antarctic toothfish caught, with that being an average of less than 250t per annum since 2016 – less than 1% of the global catch toothfish catch.

The below graph shows the IUU toothfish history over time, which has been produced from data sourced from the Scientific Committee of CCAMLR until 2010. Since 2011, CCAMLR have not officially estimated IUU toothfish catches, and so COLTO has estimated these figures based on market price and surveillance data.